John Knowles Paine (23:47):

John Knowles Paine (23:47):

Agnes van Rhijn (to Marian Brook): “Aurora Fane has invited you to the Academy of Music. You will hear John Knowles Paine conduct the Boston Symphony Orchestra.”

Marian: “That sounds fun. Will you come?”

Agnes: “I’d rather be put to death.”

Marian: “Don’t you approve of the Academy?”

Agnes: “I do, and I can manage opera as long as I can talk, but sitting through a symphony is beyond me.”

I appreciate the research and historical accuracy in this scene, as John Knowles Paine (1839-1906) was a real person and one of the first American-born composers to achieve fame for large-scale orchestral music. He was the oldest member of a group of composers known as the Boston Six, which included Amy Beach, Arthur Foote, Edward MacDowell, George Chadwick, and Horatio Parker. He studied in Berlin and toured Europe for three years giving organ recitals. Upon returning to the United States, he was appointed America’s first music professor at Harvard University in 1875. His pioneering courses in music appreciation and music theory became a model for collegiate music education in America. He was a guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in its first season in 1881.

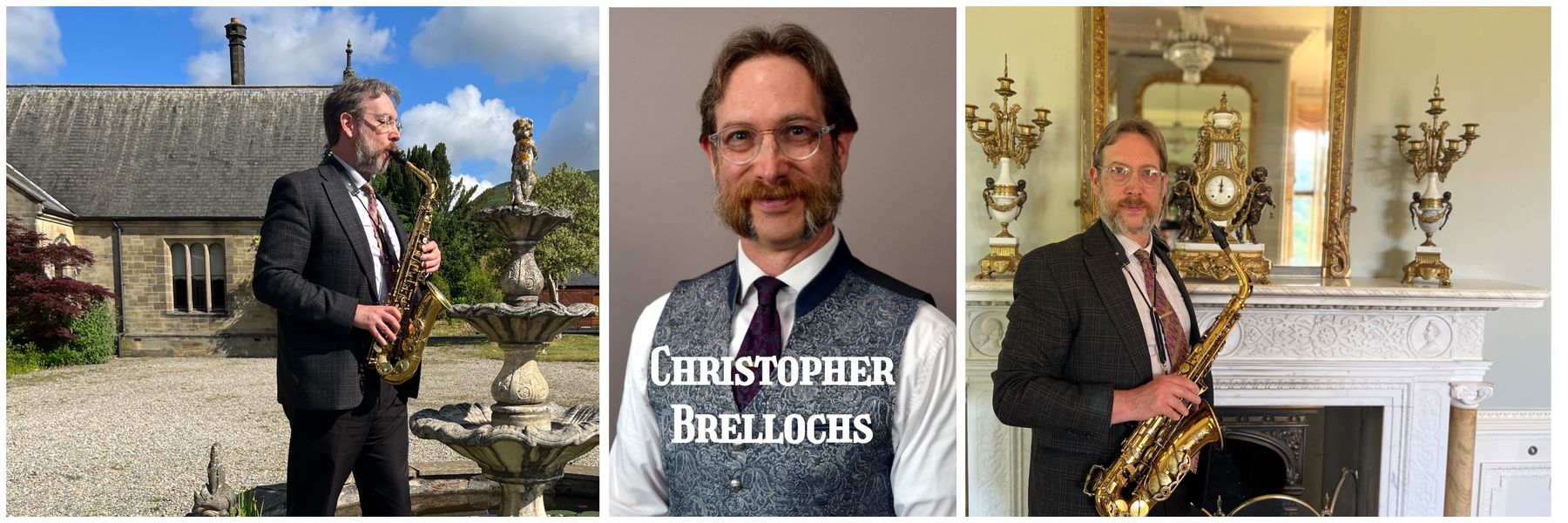

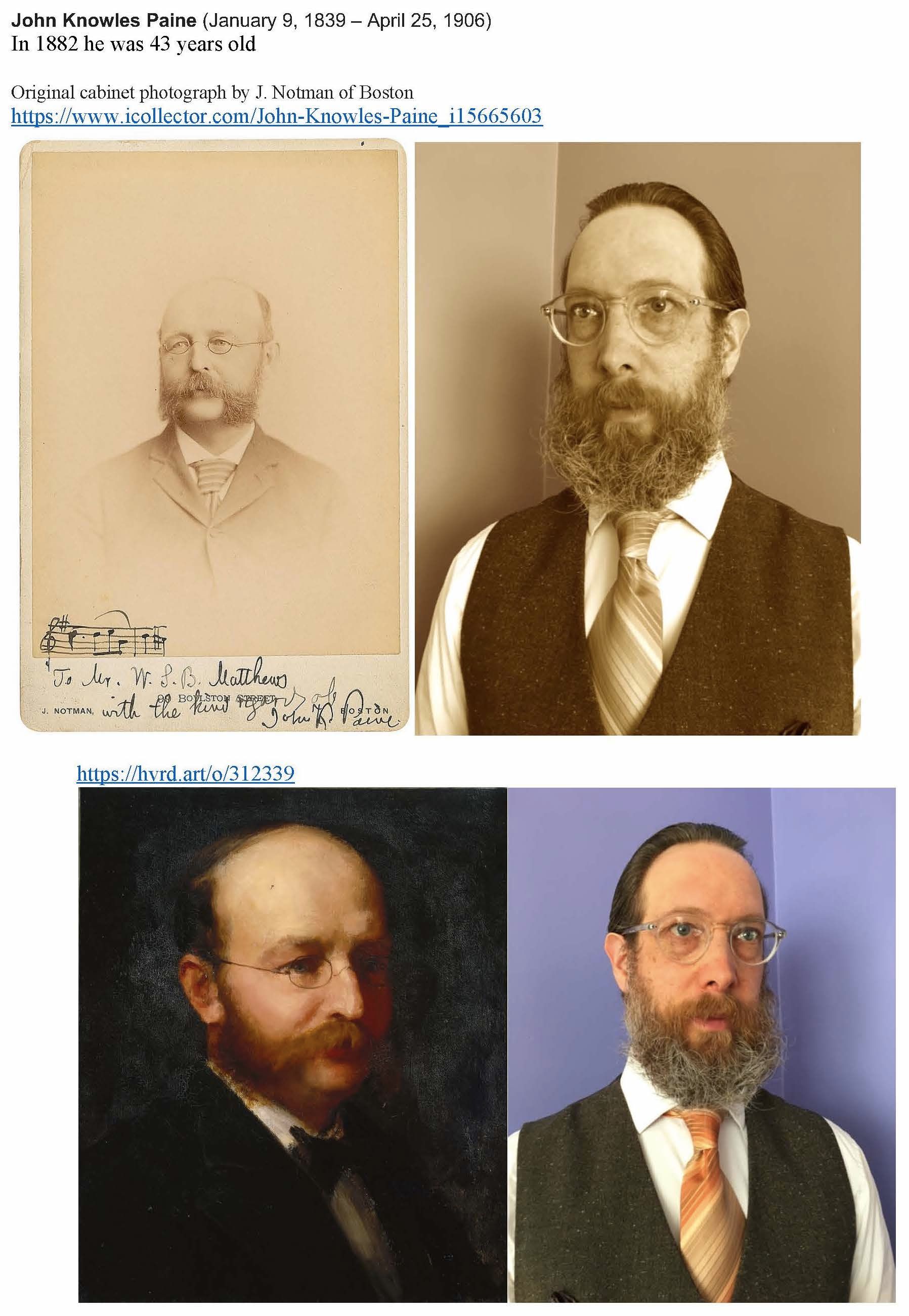

I made the above composite of images and sent it to the casting agency to convince them I could be

John Knowles Paine.

The Gavotte (25:15): Marian receives a gift from Mrs. Chamberlin but, since she won't tell Agnes who it is from, Marian decides to return the gift.

Agnes: “Marian, you would never entertain advances from someone whom I might not consider suitable?”

Marian: “’Entertain advances?’ That sounds like a dance step in the gavotte.”

The gavotte was a medium-paced French dance, popular in the eighteenth-century; interestingly, some of the most popular examples today were composed by German composer Johann Sebastian Bach.

The Academy of Music (26:00): During a meal at the Russells’ this conversation occurs:

Bertha (to George): “I had a letter from Mrs. Fane today. She means to call on me. I wondered if you knew why.”

George: “Perhaps she needs your help with a charity. Maybe it’s the business of building a new opera house.”

Bertha: “She won’t be in favor of that. She will be on the side of the Academy.”

The subject of the opera houses was introduced in Episode 3 in a conversation from the perspective of old-monied New York: Mrs. Astor, Aurora Fane, and Anne Morris. The plot thickens!

Mrs. Chamberlin’s Art (31:09): Marian Brook visits Mrs. Chamberlin to return the box she was gifted and examines a painting by Edgar Degas called The Dancing Class (ca. 1870). This was Degas’ first painting of a dance class, and the models came to his studio to pose since he did not yet have privileges to go backstage at the Paris Opéra. The painting includes an elderly gentleman with a violin leaning against a piano.

The choice to include this work of art in the series is historically appropriate; it demonstrates how influential French culture was becoming, and shows another way in which music was important during The Gilded Age.

Edgar Degas, The Dancing Class (ca. 1870).

Aurora Fane Invites Bertha Russell to the Concert (34:45):

Bertha: “Will you tell your circle of this labor you’ve undertaken?”

Aurora: “I’ll tell them we’re friends now. And to that end, I wonder of you’d join me for a concert on Friday.”

Bertha: “At the Academy of Music?”

Aurora: “Of course.”

The film location for the Academy of Music was the Troy Savings Bank Music Hall. The Troy Savings Bank moved to its current location in 1870. In appreciation of the community's support, the plans for the new building called for a music hall to be built on the upper floors.

George B. Post, a student of Richard Morris Hunt, designed the building, and his preference for the Beaux Arts and French Renaissance styles can be seen in the building's highly detailed decorations. Construction began in 1871 and was completed in 1875. The music hall has a capacity of 1,253, and most of the original frescoes are still visible.

A Grand Ball at The Academy of Music from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1871).

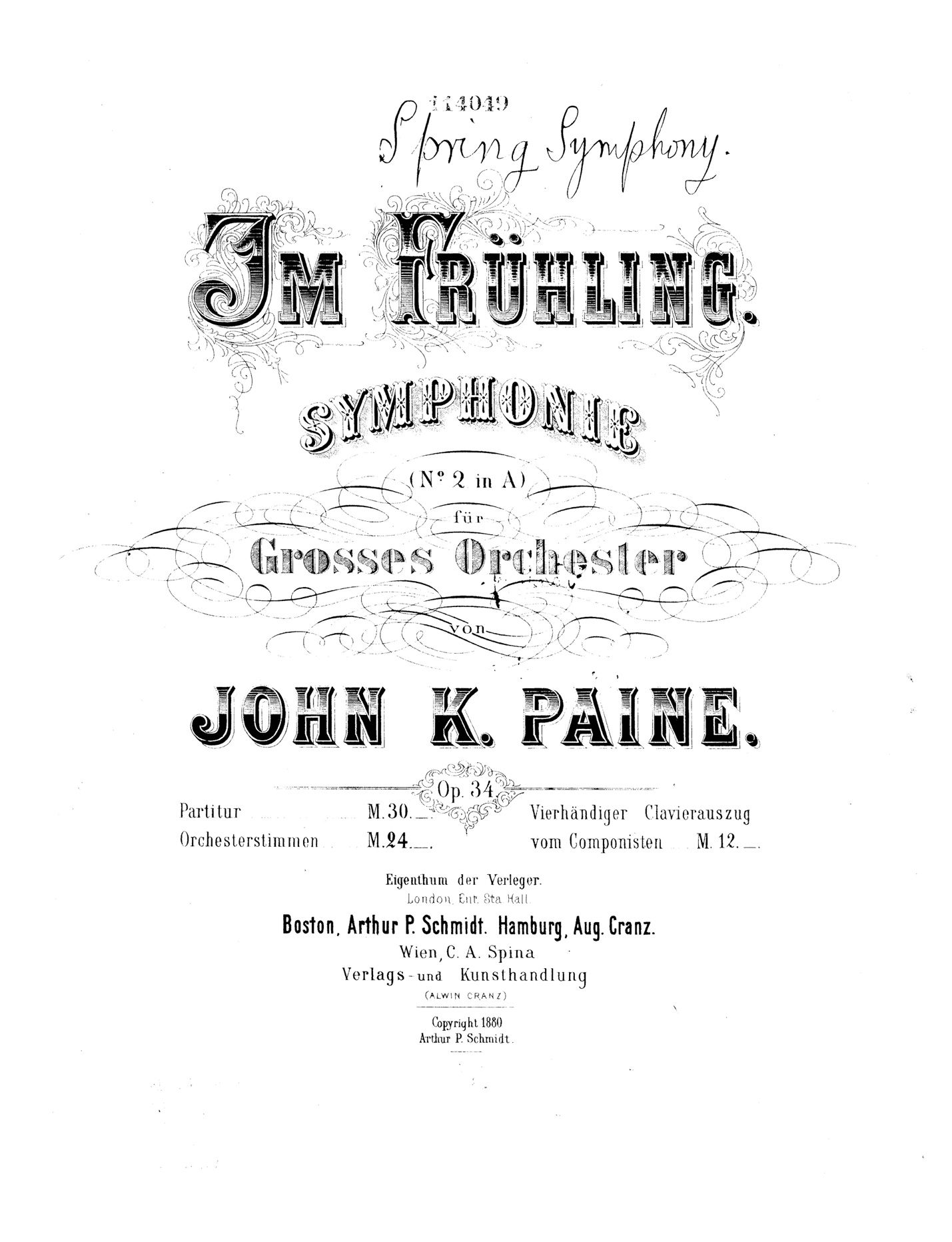

The Academy of Music Symphony Concert (50:44): In this scene we are treated to an extended performance of the last 1 minute and 31 seconds of John Knowles Paine’s, Symphony No. 2 in A: Im Frühling, II. Scherzo Allegro, May-Night Fantasy. The symphony starts as Bertha Russell descends the staircase in the Russell mansion wearing a flowing red dress with a long train.

The music then becomes underscoring for this conversation:

George: “Heavens. What a vision. The whole audience will be looking at you.”

Bertha: “You are sweet. Is the carriage here yet? Turner said she thought so.”

George: “It is. Have I seen this cloak before?”

Bertha: “I’m sure you have. But I must run. I’m terribly late as it is. And I don’t want to arrive after they’ve started.”

This last statement shows that Bertha doesn’t yet understand the social norms of old money New York, as it was common for them to show up late to performances.

The music returns to being the primary focus as Bertha leaves the mansion.

Sheet music for John K. Paine, Symphony No. 2.

(51:42) Once inside the Academy of Music, we see the orchestra performing the music with a sequence of shots in the following order: a view of the 1st violins, close-up of the timpani, a long panning shot starting with the brass and sweeping over the orchestra (including yours truly conducting) and into the audience, a shot over Marian Brook’s shoulder looking at the orchestra, back to the 1st violins, a close up of the flute, another close up of the timpani; and a shot of the orchestra over my shoulder (aka conductor and composer John Knowles Paine).

Rousing applause ensues, and we see a close-up of Marian, Bertha and Aurora Fane clapping and then another shot of the orchestra from the Fane’s box seats over the shoulders of Marian and Bertha. The lights come up for intermission and Charles Fane raises a pair of opera glasses towards the stage.

Dr. Christopher Brellochs as John Knowles Paine. Notice how my glasses frames are smaller than in the photos sent to the casting agency, and my beard has been trimmed into a Gilded Age style.

A Peek Behind the Scene

I’ve spent many years researching and performing music of the Gilded Age, so it was an absolute delight to apply my expertise in helping make the scene look as historically accurate as possible.

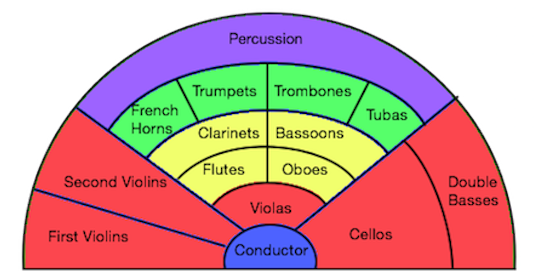

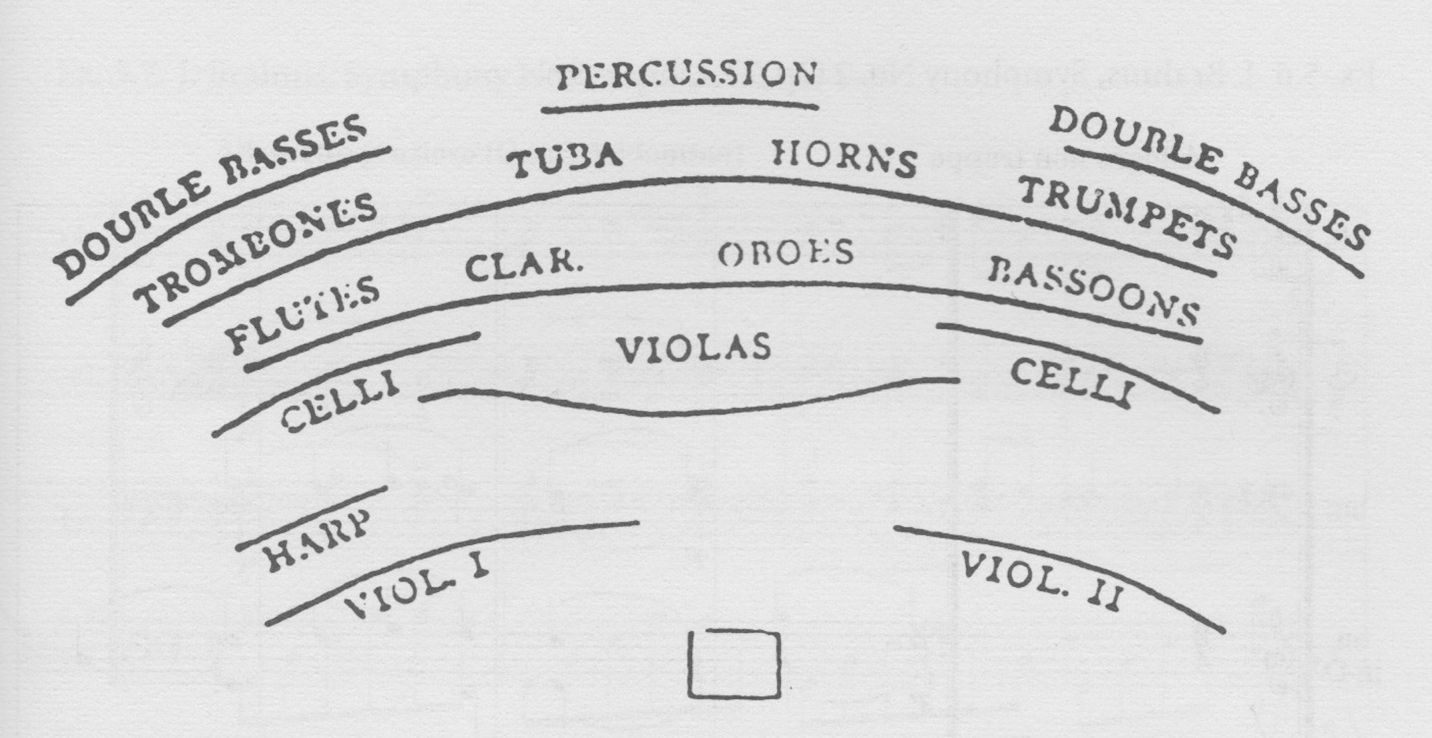

Have you ever asked, “Has the orchestra always been setup with violins, violas, and cello seated in the front going from left to right, with double basses behind the cellos, woodwinds in the second and third row, brass in the fourth row, and percussion in the back?”

Our present-day orchestra seating plan.

I asked myself that question, and it turns out musicians have tried many different configurations since the orchestra was first invented in the seventeenth-century. The scene in HBO’s “The Gilded Age” takes place in 1882 with the Boston Symphony, and in real-life the very same orchestra developed a seating plan in 1881 that adopted a very different setup compared to what is used today. The most startling difference is the use of a left/right “stereo” effect of splitting the violins, celli, and double basses. I shared this with the production team so they could setup appropriately.

Henschel’s seating plan for the Boston Symphony, approved by Johannes Brahms (1881).

Now I can hear some of you saying, “Only a few music historians would ever notice this; does it really matter?” Although many people might not know if something is historically accurate, every detail in a film or television show, from costumes, hair styles, diction, etiquette, decorative arts, music, etc., can combine to make your experience feel “real” and allow you to immerse yourself in the story. I think that because of the hard work of experts in numerous fields, this series creates a cohesive artistic experience that compellingly transports us to another time – whether the audience member can consciously identify that it is indeed historically accurate.

Unlike in some shows, this on-screen orchestra was composed of actual musicians, and we had a rehearsal on the day before where we performed the music. However, music is almost always rerecorded after filming to get the highest quality audio, so for the scene we were miming to a recording. To make it look accurate, the violin, viola, celli, and double basses removed the sticky rosin used on the bow and strings so they could actually play without making a sound.

Another aspect that was different in 1882 as compared to today was the instruments themselves. For example, the violin shoulder rest was not invented until the 1930s, and you would not have seen the colorful silk wrappings at the end of strings that you do today; the timpani membrane, or “head,” was made of calfskin instead of a plastic amalgam, and there were fewer keys on wind instruments of the past. I helped the musicians to either find period instruments, modify their instrument to look historically authentic, or work with the production team’s prop master to rent the right looking instruments.

1865 oboe on the left vs. modern oboe on the right.

(52:22) Going back to the scene, after the orchestra performs the ending of the second movement of the symphony, there is an intermission during which we hear the following:

Aurora: “Marian, please look after Mrs. Russell.”

Bertha (to Marian): “Don’t worry about me. I suppose you know plenty of people here.”

Marian: “Not at all. But I’ve read about this so often in novels.”

Speaking of musical performances appearing in novels, it is worth pointing out that Edith Wharton’s novel, Age of Innocence (1920), starts with a scene at the Academy of Music.

We catch a glimpse of the orchestra returning to their seats during this conversation:

Marian (to Thomas Raikes): “Who are you here with?”

Thomas Raikes: “Mrs. Henry Schermerhorn. She has the next box. Is this yours, Mrs. Russell?”

Bertha: “Oh no, I don’t have one.”

Aurora: “There’s a terrible waiting list.”

Bertha: “Especially for me.”

Bertha’s remarks underscore how new money was often kept out of old-money society and they set the stage for the inevitable solution – a new opera house!

Aurora: “Now for the third movement--“A Romance of Springtime,” how lovely.”

As Marian responds, we see the orchestra standing as the conductor returns to the stage.

(56:03)

The third movement of John Knowles Paine, Symphony No. 2 in A: Im Frühling

III. Adagio. A Romance of Springtime starts, and we see a shot from the boxes of John Knowles Paine conducting the orchestra and then a series of close-ups of the lead characters as this achingly beautiful music washes over them and the credits roll.